Single Views of Rome

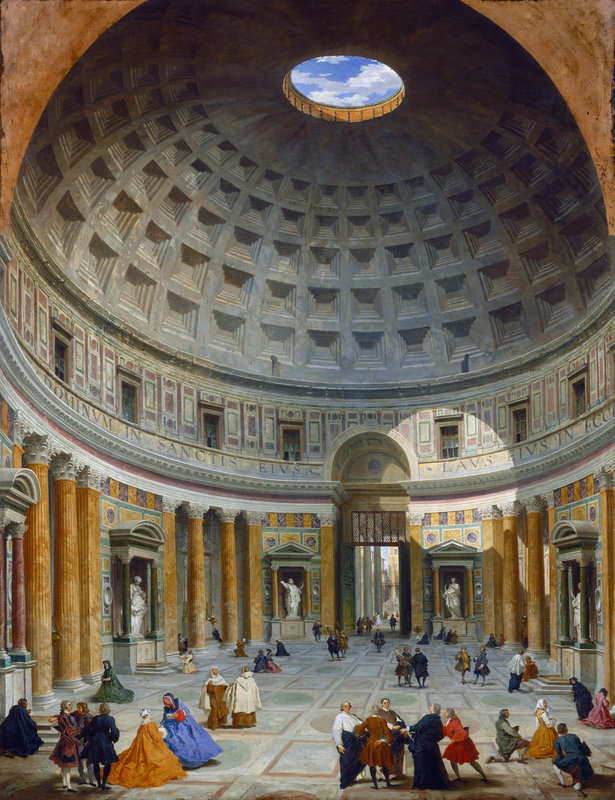

Giovanni Paolo Panini, Interior of the Pantheon, 1734, oil on canvas, Samuel H. Kress Collection

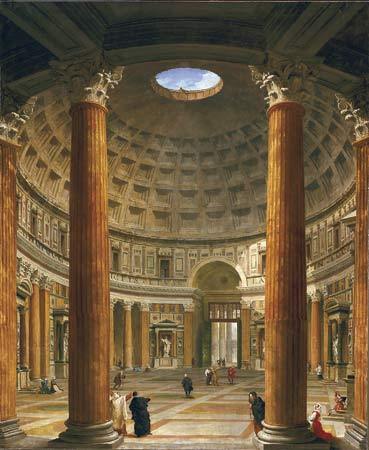

Giovanni Paolo Panini, Interior of the Pantheon, 1732, oil on canvas, In a private collection.

In addition to demonstrating skill through the creation of multi-scene paintings, Panini also conducted close studies of architectural spaces through singular views of Rome. Often, these paintings exhibited actual spaces, rather than a conglomeration of invented and real spaces as in a capriccio. Accordingly, Panini’s singular views of Rome function as more than celebrations of Roman monuments, but also as accurate, visual records of historic sites.

Among those for which he is well known is a close study of the Pantheon. The Pantheon, or “temple for the gods”, was a quintessential stop along the Grand tour during the eighteenth century. Rebuilt in 128 A.D. under the rule of Hadrian, the Pantheon remains one of the most lauded and well-conserved ancient monuments in Rome.[1] Panini’s interest in the interior space of the Pantheon was sustained for over twenty years, and manifested itself through a series of replicate paintings experimenting with light, 3-D perspective, and the placement of subjects within the space. Panini’s representations effectively evoked nostalgia for classical antiquity, while reflecting modern perceptions of Rome as a city that invests in maintaining art and architecture of the ancient world.

Panini places the gaze of the viewer in his 1732 study of the Pantheon between two Corinthian columns and directs their view across the center floor and toward the entrance of the building to the outside courtyard. Panini effectively manipulates this perspective in a second interior scene of the Pantheon painted in 1734 so that the viewer is directed toward the entrance and out into the courtyard, while simultaneously encapsulating both the oculus of the coffered dome and the elaborately tiled floor within the picture frame. Akin to a wide-angle camera lens, this theatrical, baroque perspective exaggerates the space, making it appear larger than reality.[2] A ray of light shines from the oculus, reflects off of the curved and coffered dome, floods the space, and illuminates the draftsmanship of the artist-- a reflection of the clarity with which eighteenth-century antiquarians perceived the classical past. In small clusters scattered throughout the architectural space are contemporary participants of the Grand Tour who, in relation to the grand dome, appear minute in size and serve as mere accessories to the main subject of the image--the architectural structure. The contemporary figures that Panini divisively arranges as subjects are engaged with the ancient building, thereby creating a connection between antiquity and modernity.[3],[4]

Giovanni Paolo Panini, A Ball Given by the duc de Nivernais to Mark the Birth of the Dauphin, 1751, oil on canvas, National Trust Waddesdon Manor.

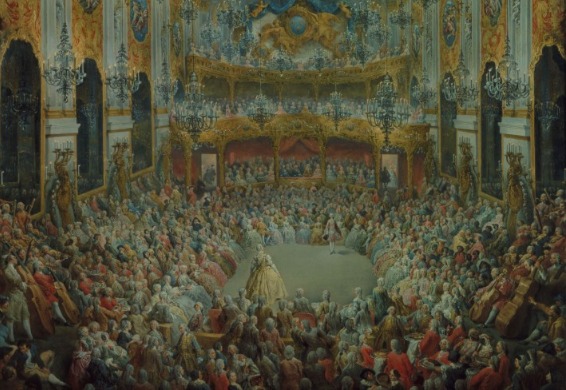

Giovanni Paolo Panini, A Concert Given by the duc de Nivernais to Mark the Birth of the Dauphin, 1751, oil on canvas, National Trust Waddesdon Manor

In the pendant paintings, A Ball (155 x 119.3 cm) and A Concert (155 x 119.3 cm), Panini recreates the Farnese Palace in Rome with vivid color and meticulous detail. He depicts an extravagant four-day celebration that was arranged by the Duc de Nivernais in 1751 to mark the birth of the Duc de Bourgogne, son of the Dauphin in France.[5],[6] The composition is marked by significant pictorial depth. Through one-point perspective, Panini offers the viewer entrance into the hall, which recedes into the background of the architectural space.

In the oil painting, titled A Concert, the viewer is positioned toward the stage and elevated above the main audience. Looking down, she can observe the large hall filled with those participating in the festivities. The audience is separated from the stage-performers by a large, decorative carpet, referencing the French royal carpet manufactory. While great in number, each subject of the painting has been awarded a high degree of attention and detail.; likewise, status and position in society is delineated by dress. For instance, those in the front row of the audience are all depicted wearing red and white hats signaling their positions as cardinals of Rome. The degree of nobility and decadence with which figures have been depicted resonates with Panini’s rendering of the architectural structure. Along the walls of the palace, ephemeral paintings that depict classical scenes are contained within gilded panels. Lining both sides of the theater under these images of antiquity are vertical mirrors—a quintessential Rococo set-up. This is furthered by the numerous chandeliers which hang from the curvilinear ceiling. Notably, the chandeliers do not provide the main source of light within the composition. Rather, a light source beams from the stage itself, lending the performance, which evidently consists of classical and allegorical figures, a sacred quality. Panini’s second painting, A Ball, captures a similarly engaging crowd within the same architectural space. The crowd, however, sits in a circular arrangement, thereby transforming the space—the room no longer recedes into the background of the composition, but rather, appears oval-shaped and stunted in size. This draws the viewer’s eyes toward the center pair of figures, who are engaged in a dance. The joyous occasion, as documented in this composition, appears to have included more than conversation between aristocrats, but also musicians and a feast. Indeed, both paintings-- A Concert and A Ball-- depart from Panini’s familiar views of Ancient Rome as they pertain to the Grand Tour. Instead, these compositions function as records of court celebrations occurring at the Farnese palace and, more broadly, of the theatricality and decadence of French culture abroad.[7]

[1] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "Pantheon." Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed May 10, 2017. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pantheon-building-Rome-Italy.

[2] Richard Paul Wunder, "Panini's View of Roman Monuments." Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 56, no. 268 (1961): 54-56. doi:10.2307/3795133.

[3] Wixom and Linsey, 263.

[4] Wilkin, Karen. "Roman holiday." New Criterion 18, no. 9 (2000): 24. Biography in Context, accessed May 9, 2017. http://libraries.state.ma.us/login?gwurl=http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A62649865/BIC1?u=mlin_m_wellcol&xid=e63d98af.

[5] Dickinson, "A Concert (one of a pair)," accessed May 10, 2017, http://www.simondickinson.com/artwork/a-concert-one-of-a-pair/.

[6] Dickinson, "A Ball (one of a pair)," Dickinson, accessed May 10, 2017, http://www.simondickinson.com/artwork/a-concert-two-of-a-pair/.

[7] "New paintings at Waddesdon Manor: recent acquisitions for the Rothschild collection: the collections at Waddesdon have been enhanced by the recent acquisition of four major paintings, by Callet, Chardin and Panini," The Free Library, accessed May 10, 2017, https://www.thefreelibrary.com/New paintings at Waddesdon Manor%3A recent acquisitions for the...-a0185291649.