The Goals and Allure of the Grand Tour in Italy

The excavations at Herculaneum and Pompeii, which began in 1738 and 1748 respectively, played a major role in the development of European taste, in part thanks to the relative inaccessibility of classical remains in Turkish-ruled Greece and Asia Minor. Neo-classical excitement and enthusiasm, not to say hype, in the 1770s and 1780s about the discoveries was very influential. There were also important excavations in and around Rome. The Neo-classical painter and archaeologist Gavin Hamilton excavated Hadrian's villa at Tivoli in 1769. The sculptures and other remains that were discovered in such excavations helped to bring an important revival of aesthetic appeal to interest in the classical world.1

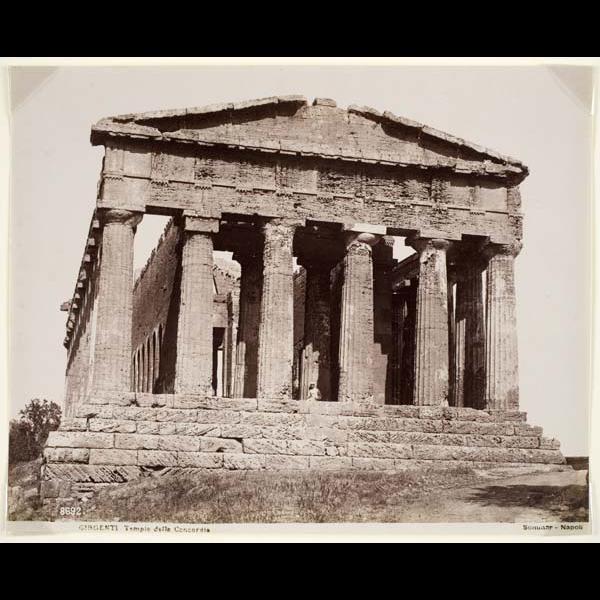

Tourists did not flock to Italy for its large, modern cities as much as they did for its ruins, especially since the baroque, the elaborate and dramatic style of the seventeenth century, was seen as outdated by mid-eighteenth century, which was around the same time that the ruins were being excavated.

In addition to claiming many antiquities, Italy was further south than most other Grand Tour destinations: France and Germany, for example. Tourists preferred its temperate climate since the average tour lasted about three years.2 Thus, in addition to being an intellectual experience, the Grand Tour in Italy also marked the beginning of travel for pleasure. Italy also did not participate in any of the recent wars that France and Britain engaged in just before the height of the Grand Tour which included the Nine Years’ War (1689-97) and the War of Spanish Succession (1702-13).3 This made travel more pleasant for tourists hoping to avoid any political conflicts. Therefore, the Grand Tour in Italy was able to reach its height in the mid-eighteenth century because of this peace in Italy in addition to the excitement built around the excavation of Roman ruins.

__________________________________________________

1. Jeremy Black, “Italy and the Grand Tour: The British Experience in the Eighteenth Century,” Annali d'Italianistica 14, (1996): 532–541.

2. Jeremy Black. Italy and the Grand Tour. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 4.

3. Ibid., 2.