Women and the Grand Tour

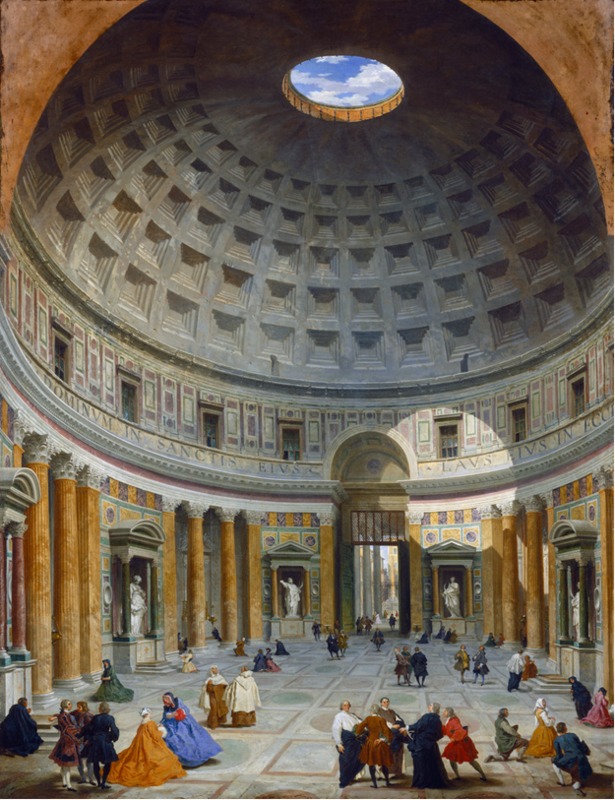

Giovanni Paolo Panini, Interior of the Pantheon, Rome, c. 1734, oil painting, (National Gallery of Art)

Unsurprisingly, European women from outside of Italy were not able to travel in the same way that men could. Recalling how the Grand Tour was considered the final touch to a man’s education, the Grand Tour was not considered necessary for women since they did not have access to the same level of education as men for the most part, in particular in England and France. Still, some women managed to accompany “husbands, sons, brothers, and parents” although they would not be reaping the same benefits. As professor of Italian literature Elizabetta Graziosi states, “This was part of a more general impediment which kept women far from the loci of culture and from the means of procuring culture: books, travel, good instructors, and the frequenting of cultures persons in a manner not directed aimed at marriage…”1 Within Italy, women were offered a complete education and were able to participate in discourse as much as men.

The amazement educated women caused male tourists says a lot about what other Europeans felt about educated women. Marta Cavazza, an Italian historian focusing on women and scientific institution, retells some accounts from Lettres d’Italie by Charles De Brosses, who was an 18th-century Grand Tourist from France. Apparently, De Brosses was astonished by encountering many female intellectuals in Italy: While visiting Milan in 1739 he wrote that he found it “singular” or extraordinary to see women such as the young poet Francesca Manzoni among the educated men.2 Other female intellectuals he encountered included the Countess Clelia Grillo Borromeo, patron of philosophers and academies; Maria Gaetana Agnesi, “daughter of a rich bourgeois” who “discussed in Latin and French the mechanisms of sensation and imagination, light and colors, the transparency of bodies, and the properties of certain geometric curves”; and Laura Bassi, another philosopher with a degree who would give lectures at the university in Bologna.3 In reference to the women, De Brosses described Bassi’s professorship as not “decent” and thought Agnesi’s conversation in Milan was ostentatious. Cavazza notes that many European tourists like De Brosses were surprised by the knowledge and fame of Italian women but that they also wrote it off as an Italian “phenomenon.”4 Therefore, De Brosses’ native France must provide the same opportunities for women since he found women’s participation in academia strange.

____________________________________________________________

1. Elisabetta Graziosi, "Revisiting Arcadia: Women and Academies in Eighteenth-Century Italy," in Italy's Eighteenth Century: Gender and Culture in the Age of the Grand Tour (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2009), 103.

2. Marta Cavazza, "Between Modesty and Spectacle: Women and Science in Eighteenth-Century Italy," in Italy's Eighteenth Century: Gender and Culture in the Age of the Grand Tour (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2009), 275.

3. Ibid., 277.

4. Ibid., 278.