Coins: the Temple through Time

In its thousand year history, the Temple of Jupiter was destroyed or damaged and rebuilt four times, largely replicating the original structure.1 Coins show us roughly contemporary depictions of the Temple.

FIRST TEMPLE

The original Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus dedicated in 509 BCE lasted until 83 BCE, when it was completely lost to fire. In 69 BCE, the consul Q. Lutatius Catulus dedicated the reconstruction of the Temple. Therefore, the 78 BCE coin, made between these dates, must be a memory or imagining of the temple, not necessarily a faithful reproduction of the structure. The coin is shown as a Tuscan tetrastyle (four columns), with the three cellae (temple chamber) doors clearly represented.2 The thunderbolt on the pediment (above the door) is a common symbol found on coins depicting any temple of Jupiter, but the actual pediment did not have any decoration.

Depiction of the second Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus on a denarius coin, 41 BCE.

Depiction of the second Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus on an as coin, 69 CE.

SECOND TEMPLE

In 26 BCE, the temple was struck by lightning and damaged, then repaired by Augustus, only to experience more lightning damage in 9 BCE. On this 41 BCE coin, the Temple is shown as a hexastyle (six columns) temple, in Tuscan style, even though it was actually Corinthian at this point in time.3 Faint outlines of what appear to be the three cellae are visible between the columns.

On the 69 CE coin, struck just before the fire later that year, figures on the façade of the tetrastyle temple and the cult statue of Jupiter are clearly represented. The maker of the coin left out the two central columns to show the cult-statue of Jupiter, and does not show the cult-statues of Juno Regina and Minerva.4 The pediment reliefs cannot be identified.5

THIRD TEMPLE

Following its consumption by fire in 69 CE, the emperor Vespasian rebuilt the Temple in 70-79 CE, only to have it burn down again in 80 CE. On the 71-73 CE coin, the temple is shown as hexastyle, and heavily decorated. The coin clearly depicts figures on the façade and revetments (sloping roof), statues around the temple, and cult statues of Jupiter, Juno Regina, and Minerva inside the temple. On the corners of the roof are eagles, a symbol of Jupiter. In 82 CE the emperor Domitian dedicated the final reconstruction of the Temple.

Depiction of the fourth Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus in tetrastyle, with cult statues of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva between the columns, on a cistorphorus coin, c. 82 CE.

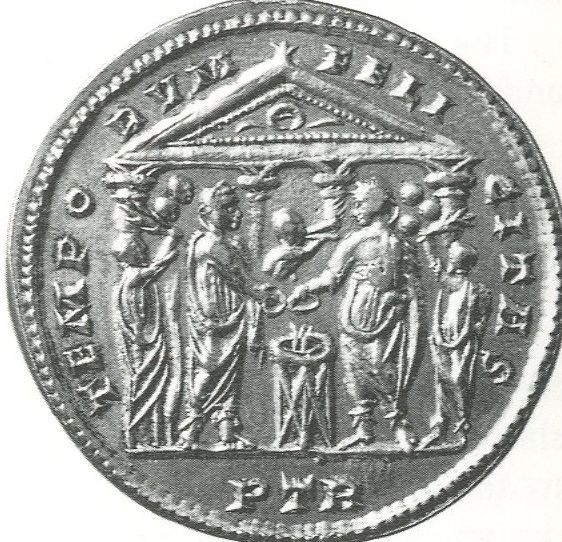

Depiction of the fourth Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus on a 4-aurei piece coin, 305 CE.

FOURTH (FINAL) TEMPLE

The final Temple lasted until 455 CE, when the Vandals plundered Rome and destroyed the Temple. The 82 CE coin, with the Temple represented as tetrastyle, shows the cult statue of Jupiter flanked by cult statues of Juno Regina and Minerva, with elaborate decorations on the pediment and roof.6 The 305 CE coin shows a scene of a sacrifice before a tetrastyle temple, which the oak-wreath identifies as the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus.7 The four columns are simplified from six due to artistic license.

After the destruction of the Temple in 455 CE, it is unclear what this area of the Capitoline Hill was used for.8 In the twelfth century CE it was used for government. Today, ruins of the foundation walls of the Temple can be found in the Musei Capitolini in Rome (at left).

1 Amanda Claridge, Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 268-270; John W. Stamper, The Architecture of Roman Temples (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 125, 151-156; Philip V. Hill, The Monuments of Ancient Rome as Coin Types (London: Seaby, 1989), 24-26; L. Richardson, jr., A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Baltimore: the Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 223.

2 Philip V. Hill, The Monuments of Ancient Rome as Coin Types (London: Seaby, 1989), 24.

3 Philip V. Hill, The Monuments of Ancient Rome as Coin Types (London: Seaby, 1989), 25.

4 Philip V. Hill, The Monuments of Ancient Rome as Coin Types (London: Seaby, 1989), 25.

5 Philip V. Hill, The Monuments of Ancient Rome as Coin Types (London: Seaby, 1989), 25.

6 Nathan T. Elkins, Monuments in Miniature: Architecture on Roman Coinage (New York: The American Numismatic Society, 2015), 146.

7 Philip V. Hill, The Monuments of Ancient Rome as Coin Types (London: Seaby, 1989), 26.

8 Amanda Claridge, Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 261.