Introduction

Emily Zhao

“The only way for us to become great, or even inimitable if possible, is to imitate the Greeks.”1

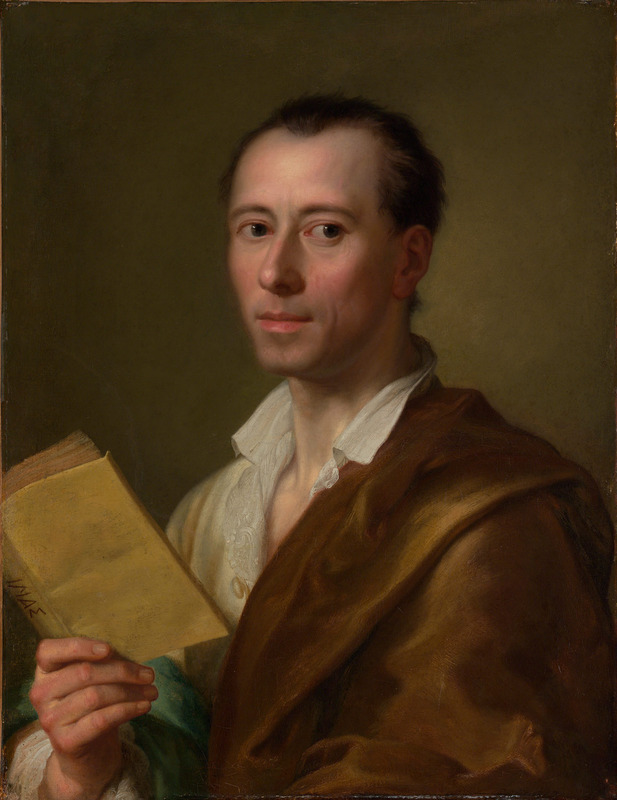

–Johann Joachim Winckelmann

The modern discipline of art history is founded upon the dialogue between style and historical context, positing a progression of well-defined styles formed by the cultural concerns of their historical moment. This conception of a cultural-historical model of art history owes much to the work of the prominent 18th century German scholar Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768). Winckelmann’s writing on Greek and Roman antiquity in his seminal 1764 work, The History of the Art of Antiquity, was instrumental in precipitating a shift from thinking of Classicism as a source of virtue and good taste, to a legitimate discipline concerned with tracing the development of Greek civilization, of which the finest Classical sculptures or fragments were believed to be representative objects.

Thus, by defining objects as products of their particular time, one of Winckelmann’s chief contributions was to historicize Classicism, transforming it from a timeless ideal to the basis of a modern discipline. Winckelmann’s efforts to define a progression within Greek and Roman styles placed Greek antiquity at the peak of human achievement, articulating a passionate apologia for the value of studying Greek art. His writings, often characterized by a peculiar investment in emotional responses to art, as well as considerable attention to the representation of physical beauty, also inaugurated a specific mode of art criticism that has raised the question of the place of emotional or aestheticizing responses within the practice of connoisseurship and criticism.

Finally, Winckelmann’s classification scheme was largely responsible for advancing the notion of Greco-Roman supremacy in human culture and aesthetic achievement, an opinion that persists even within more comprehensive art historical frameworks today. As classicist Katherine Harloe has suggested, many of the issues raised by his life story and work have made him an “uncomfortable ancestor” for generations of scholars.2 I will explore this topic, and others relating to Winckelmann’s work and legacy, in the following sections.

1 Johann Joachim Winckelmann, “Reflections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks,” (Eighteenth Century Collections Online, 2003).

2 Katherine Harloe, Winckelmann and the Invention of Antiquity: History and Aesthetics in the Age of Altertumswissenschaft (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), xxii.