Antiquarianism: The Construction of Museum Studies in Eighteenth Century Grand Tour Collecting

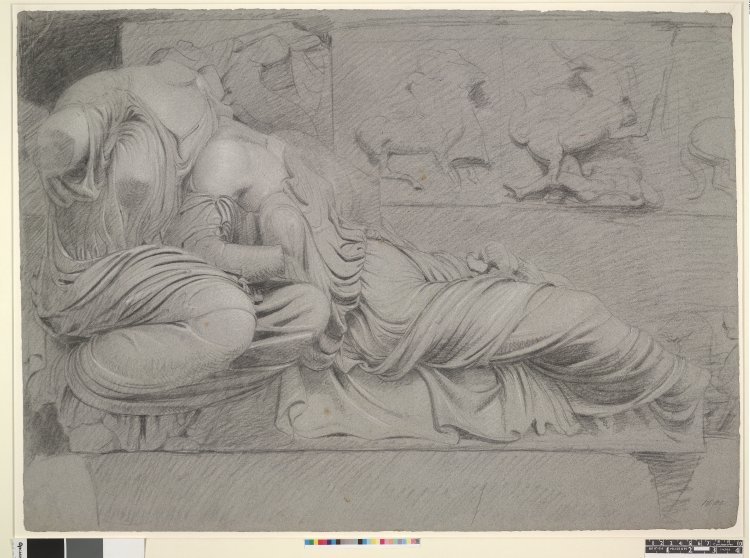

Figure 1. James Ward, Study of Sculpture: from the Elgin Marbles. Undated. Graphite on medium, smooth, cream wove paper. Repository: Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

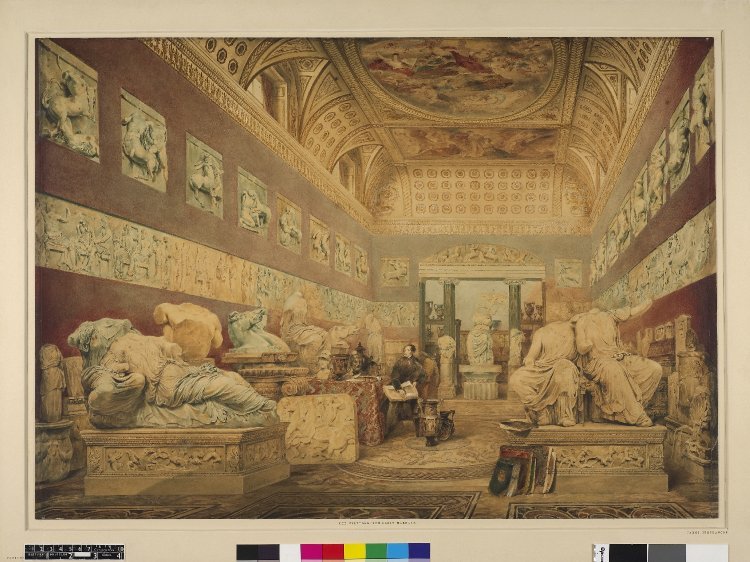

Figure 2. James Stephanoff, A fanciful arrangement of one of the British Museum’s Galleries, with pieces of the Phigaleian frieze, metopes from the Parthenon and other pieces from the Elgin collection (Elgin Marbles). c. 1819. Watercolor on paper. Repository: British Museum

Figure 3. James Stephanoff, The Virtuoso. 1833. Drawing on paper. Repository: British Museum

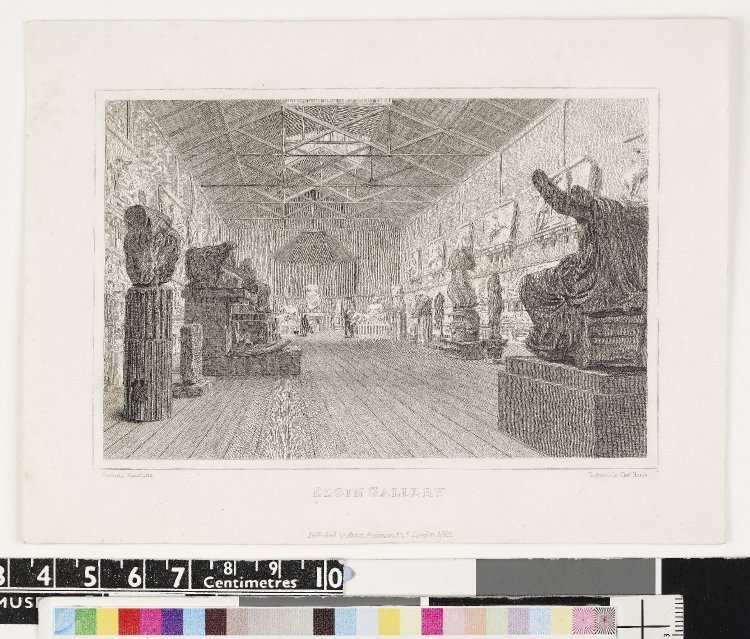

Figure 4. Frederick Mackenzie (design) and Charles Heath (print). Views of London and its Environs Series: Elgin Gallery. 1825. Etching on paper. Repository: British Museum

Figure 5. Edward Radclyffe. British Museum, Elgin Room. 1844. Line engraving on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper. Repository: British Museum

Figure 6. Robert Haydon. Untitled drawing study of the Elgin Marbles. 1809. Black and white chalk on paper. Repository: British Museum.

Increased access to Greece provided more opportunities for scholars and traveling aristocrats to carefully observe classical art and possibly take back any antiquities as a memento of their time spent in Greece. As previously mentioned, Thomas Bruce, the Seventh Earl of Elgin and British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, traveled to Constantinople in 1799 with the goal of “revolutionizing English appreciation of Greek architecture and sculpture.”1 In order to accomplish this, Elgin employed British artists with the task of making casts and sketches of the Greek sculpture and architecture. They mostly completed this fieldwork in Athens, specifically in the Acropolis. Although this area was heavily guarded by Turkish and Ottoman soldiers, the group was able to bribe these men and gain access to the Acropolis; they remained in Athens until the threat of French invasion reached the city.2 A few months later, Elgin returned with permission from the Ottoman government to continue the archaeological work in Athens. After questionable methods of excavation and art dealing, Elgin’s team was able to remove one of the Caryatid sculptures from the Erechtheum and marble reliefs from the Parthenon at the Acropolis.3 These so-called “Elgin Marbles” have since been wrapped up in British and Greek nationalist politics and agendas. The Elgin Marbles have been displayed at the British Museum since 1817 and are one of the prized possessions of the institution.4 The acquisition of these marbles can be perceived as a way to reinforce their cultural superiority in Europe; although these marbles represent the artistic achievement of Greek civilization, London has employed these marbles in the marketing of its city and cultural identity (Fig. 6-7). James Stephanoff’s A fanciful arrangement of one of the British Museum’s Galleries and The Virtuoso depict scenes of the Elgin Marbles displayed in the British Museum amongst crowds of British visitors (Fig. 2-3); these images exemplify the fascination with the Elgin Marbles, or with the ideals of classicism itself, amongst the British public. The etching of the Elgin Marbles galley in Views of London and its Environs Series: Elgin Gallery demonstrates how these antiquities became wrapped up in Britain’s national identity (Fig. 4). Although the Elgin Marbles were produced in Athens, Greece, they have been passed off as important “view of London” and cultural component of the city. The acquisition of the Elgin Marbles was a form of intellectual imperialism, or the appropriation of elements of a foreign culture by scholarly means to promote one’s own nationalistic ideals. By owning some reliefs from the Parthenon, Britain is able to align itself to the magnificence of the ancient Greek Empire.

With the acquisition and display of the Elgin Marbles by the British Museum, France felt the need to “make up for lost time” with regards to its archaeological expeditions and discoveries.5 During the French Revolutionary Wars, France had acquired numerous works of art for the Louvre as spoils of war; at the conclusion of the conflict France had to return over 5000 pieces, leaving the museum empty of the majority of its collection of antiquities.6 As a result, the French government dispatched teams of explorers, scholars, and artists to survey antiquities in Greece and the Near East. One of these expeditions was that of Auguste de Forbin (1777-1841), and orphaned nobleman and artist. After the French Revolution, Forbin’s family lost their fortune and his father was hung at the Lyon gallows; luckily he was taken into the tutelage of artist Jean-Jacques de Boissieu (1736-1810), fostering his growing love for the arts.7 After several trips to Italy to study classical arts, Forbin was “appointed Director-General of Museums” and placed in charge of an expedition to the Near East and Egypt; in addition to “reorganize[ing] and redesign[ing] the museum, he was tasked with bringing back antiquities that could be added to the Louvre’s collection.8 Beginning in 1817, this trip consisted of travel throughout Greece and the Greek Isles, Anatolia, Palestine, and Egypt.9 While in Greece, Forbin led a series of unsuccessful excavations at the Piraeus. Like Forbin’s expedition, many of those on these journeys either sought to bring back antiquities or other items as souvenirs of their travels. Grand Tourist John Morritt of Rokeby states that, “some we steal, some we buy,” when referring to the common Grand Tour practice of amateur archaeology while traveling.10 The items brought back from many of these travels, most notably the Elgin Marbles, line the halls of major Western museums throughout Europe and the United States. Travel journals and publications such as those left by Auguste de Forbin and John Morritt containing information on the different ruins and monumental sites from Grand Tour routes also provided early and modern archaeologists with precious primary sources and firsthand accounts on the eighteenth century collection of antiquities.

1. Robert Eisner, Travelers to an Antique Land (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1991), 91.

4. British Museum, “The Parthenon Sculptures,” Accessed April 7, 2017, http://www.britishmuseum.org/about_us/news_and_press/statements/parthenon_sculptures.aspx

5. Charles Foster, ed., Travellers in the Near East, (London: Stacy International, 2004), 109.