The Grand Tour in Greece: An Affirmation of Classicism in European Arts Education

Figure 1. Pierre Henri de Valenciennes. Landscape of Ancient Greece. 1786. Oil on canvas. Repository: Detroit Institute of Arts (Detroit, Michigan, USA)

Figure 2. Antoine Watteau, Pilgrimage to the Island of Cythera. 1718. Oil Painting.Repository: Musee du Louvre

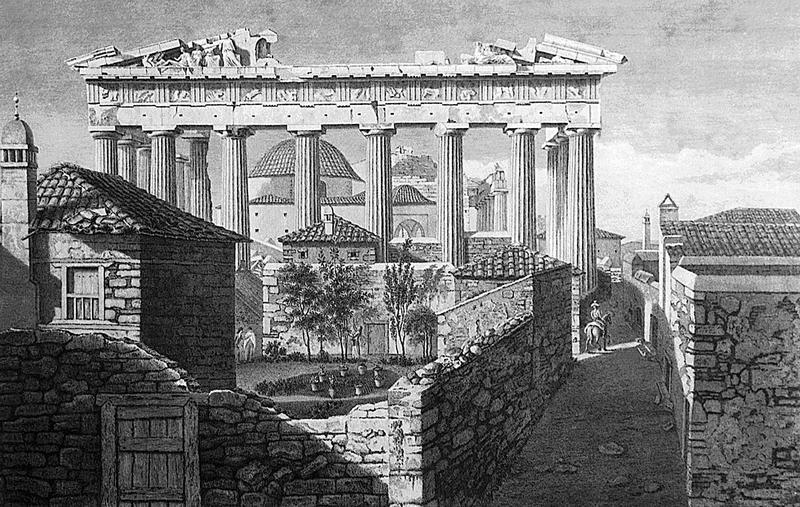

Figure 3. Nicholas Revett. The Parthenon When It Contained a Mosque, from James Stuart’s Antiquities of Athens. 1789. Drawing. Wellesley College Visual Resources Collection.

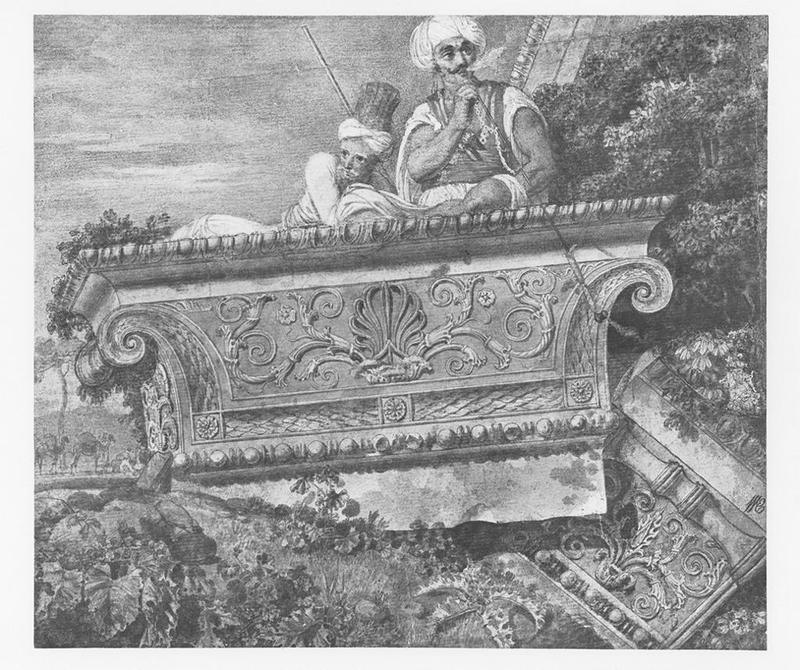

Figure 4. William Pars, Capitals of Pilasters from the Temple of Apollo Didymaeus, near Miletus. 1765. Watercolor, some pen and gray ink, made up of several small pieces of paper stuck together. Repository: British Museum

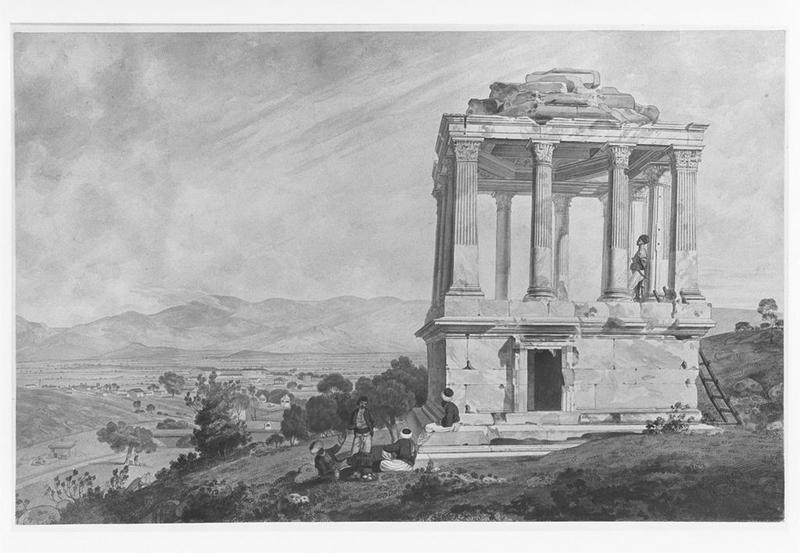

Figure 5. William Pars, Sepulchral Monument at Mylasa. 1764-65. Pen and gray ink, with watercolor, and some gum Arabic on paper. Repository: British Museum

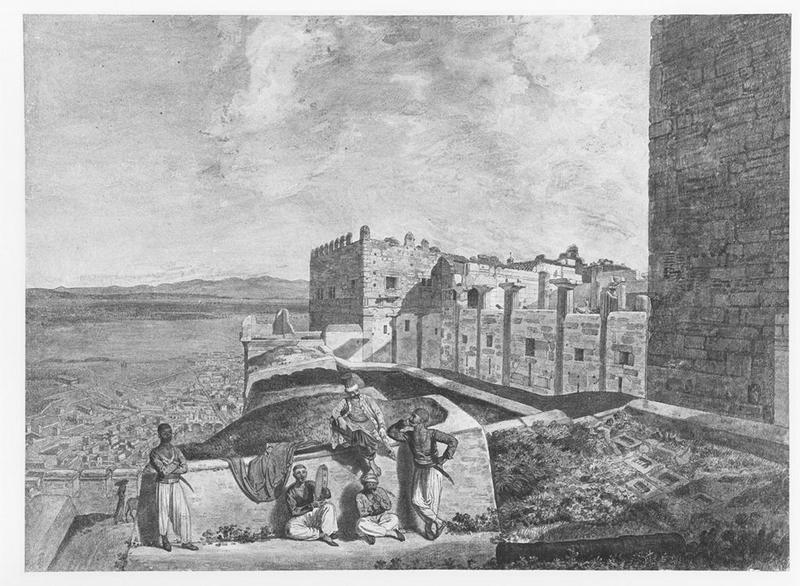

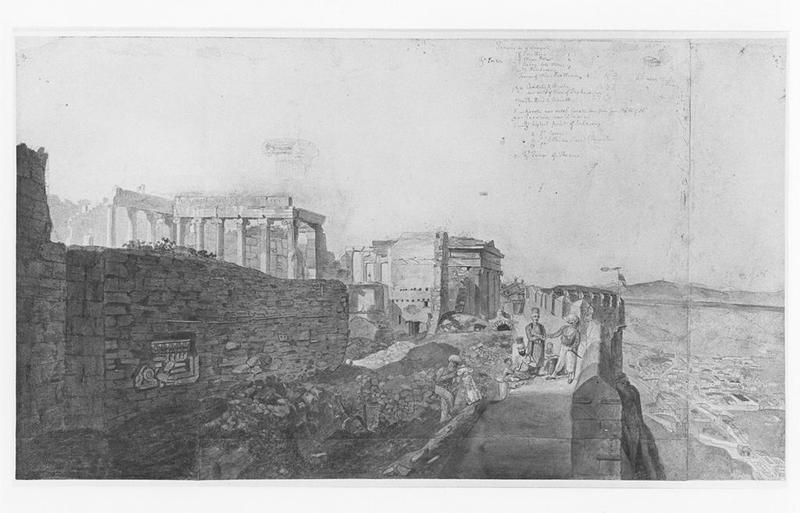

Figure 6. William Pars, The Propylaea from the Southeast. 1764-65. Pen and gray ink and watercolor, gum Arabic on paper. Repository: British Museum

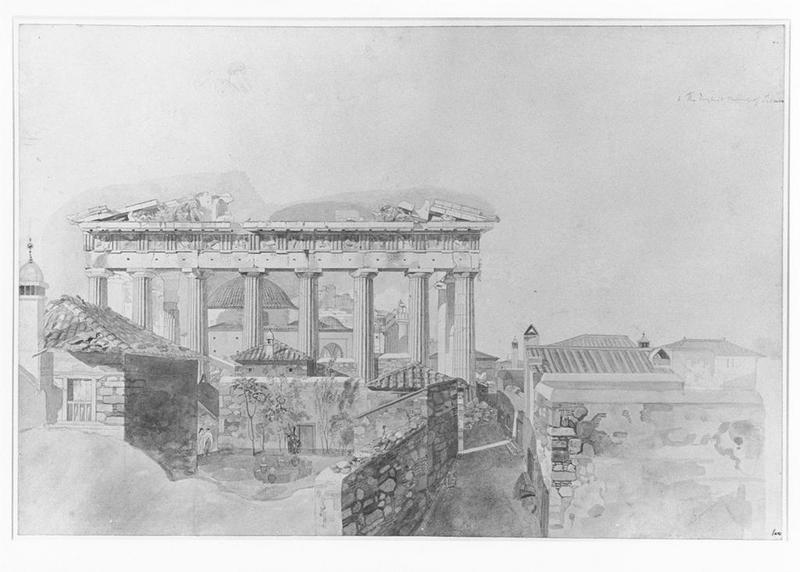

Figure 7. William Pars, East Front of the Parthenon. 1765. Pen and gray ink and watercolor, with bodycolor over graphite on paper. Repository: British Museum

Figure 8. William Pars, The Erectheum from the Northeat. 1765. Brush drawing in gray and brown wash, with watercolor, some gum Arabic, over graphite on several sheets conjoined.Repository: British Museum

With the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars in the early nineteenth century, Grand Tourist routes to Italy through France became extremely dangerous, and there was a need for new destinations that still satisfied the hunger for knowledge of Greco-Roman culture. Roman and Greek societies were considered by these nobles as the origins of Western civilization. By aligning themselves with Roman and Greek achievement, French and British nobility were able to position themselves next to the founders of such civilization. At the time, royal academies of art were also looking to classical art forms as the highest standards of beauty; figural depictions in history paintings mimicked the way in which the human form was rendered in Greek sculpture. Greece and Mediterranean locales were often used as the backdrops of French Academy paintings such as Pierre Henri de Valenciennes’s Landscape of Ancient Greece (Fig. 1). The use of classical art and sculpture was also a trait of in fête galante genre as demonstrated by Antoine Watteau’s Pilgrimage to the Island of Cythera (Fig. 2). Pilgrimage to the Island of Cythera depicts a scene of couples as they journey to the mythical destination of Cythera. To the far left in the painting are clusters of cupids in the sky flying above the joyous scene. To the left of these cupids are also two classical sculptures, one of a winged woman, possibly the personification of Victory or Nike, and a male figure. The Watteau’s use of Greco-Roman sculpture and elements from classical mythology in Pilgrimage to the Island of Cythera heightens the merry and cheerful mood of the painting, a key characteristic of fete galantes.

In addition to the influence of the royal art academies on the rise of classicism in the fine arts, private societies also played a key role in the dissemination of classical art ideals. A growing interest in Greece had developed as multiple scholars embarked on their own Grand Tours sponsored by aristocratic art societies. Organizations such as the Society of Dilettanti sponsored numerous trips to Greece in order to record archaeological ruins from ancient Greek society.1 Founded in 1736, the Society of Dilettanti was composed mostly of young wealthy men who had traveled to Italy. In 1751, the Society of Dilettanti dispatched architect-painter James Stuart and architect-draughtsman Nicholas Revett to Greece in order to study classical architecture in an attempt to develop an alternative style to the popular Palladian aesthetic.2 After their journey, Nicholas and Revett published The Antiquities of Athens in 1762 featuring illustrations of Athens’s ancient ruins (Fig. 3). Publications such as these increased the British appetite for classicism. Nicholas Revett also traveled with Richard Chandler and William Pars from 1764 to 1766 on an expedition to Asia Minor. As the draughtsman of the expedition, William Pars completed multiple ink and watercolor pieces surveying the landscapes and architectural ruins of their surroundings (Fig 4-8). Pars was able to capture the essence of antiquities and architecture while still illustrating how these ancient ruins fit into contemporary Greek life. In Sepulchral Monument at Mylasa (Fig. 5), Pars depicts a few men leisurely siting on the monument’s steps and leaning on its columns; Similarly, Pars captures two men reclining on the ruins of a capital in Capitals of Pilasters from the Temple of Apollo Didymaeus, near Miletus (Fig. 4). The only images that almost appears free of markers of contemporary Ottoman life is East Front of the Parthenon (Fig. 7); this watercolor is free of any visible figures and only depicts the ruins of the Parthenon.

Noblemen often traveled to Greece with employed artists, ready to capture any traces and remains of classical architecture and sculpture. The Seventh Earl of Elgin, Thomas Bruce, traveled to Constantinople and Greece in 1799.3 Before he left, he hired artisans to draw the architecture and make plaster casts of the Greek sculptures.4 These sculptures, now known as the Elgin Marbles, reside in the British Museum and are a point of pride for the British government and its archaeological achievements. The development of Grand Tour routes in Greece signifies a sustained fascination with classical ideals initiated by earlier Grand Tour travel in Italy.