The Grand Tour in the Holy Lands

Figure 1. Lewis Vaslet (design) and William Ridley (print), Patrick Russell M.D. F.R.A. 1811. Stipple on paper. Repository: British Museum

Figure 2. Nathaniel Dance (design) and Thomas Trotter (print), Alexander Russell M.D. F.R.S. c. 1786. Stipple and etching on paper. Repository: British Museum

Figure 3. Philippe de Champaigne, View of Jerusalem with the Temple of Solomon. 17th Century. Red chalk on two attached sheets of off-white laid paper. Repository: Metropolitan Museum of Art

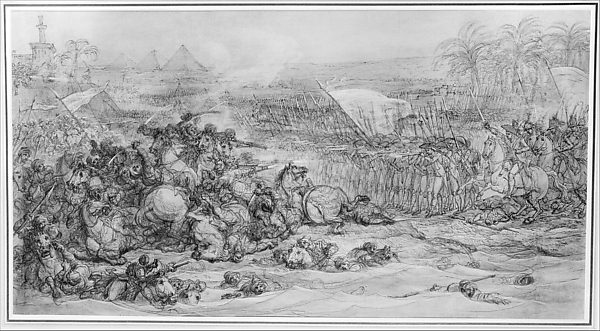

Figure 4. François André Vincent, Battle of the Pyramids, July 21, 1798. c. 1800. Pen and black ink, brush and brown wash, heightened with white on beige washed paper. Squared in graphite. Repository: Metropolitan Museum of Art

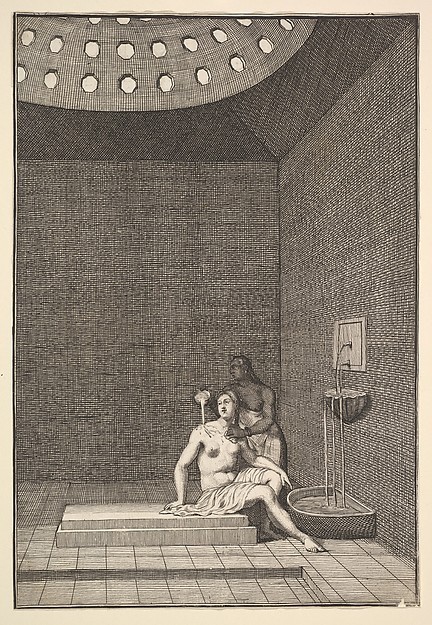

Figure 5. William Hogarth, A Turkish Bath (Aubry de La Motraye's "Travels throughout Europe, Asia and into Part of Africa...," London, 1724, vol. I, pl. 10). 1723-1724. Etching and engraving. Repository: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Figure 6. Claude Augustin Duflos le Jeune, Sultana Reading in the Harem. 1746-47. Etching and engraving. Repository: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Figure 7. Joseph Vernet (design) and Richard Purcell (print), A Turkish Lady at the Bath. c. 1759-1760s. Mezzotint, Hand-colored etching on paper. Repository: British Museum

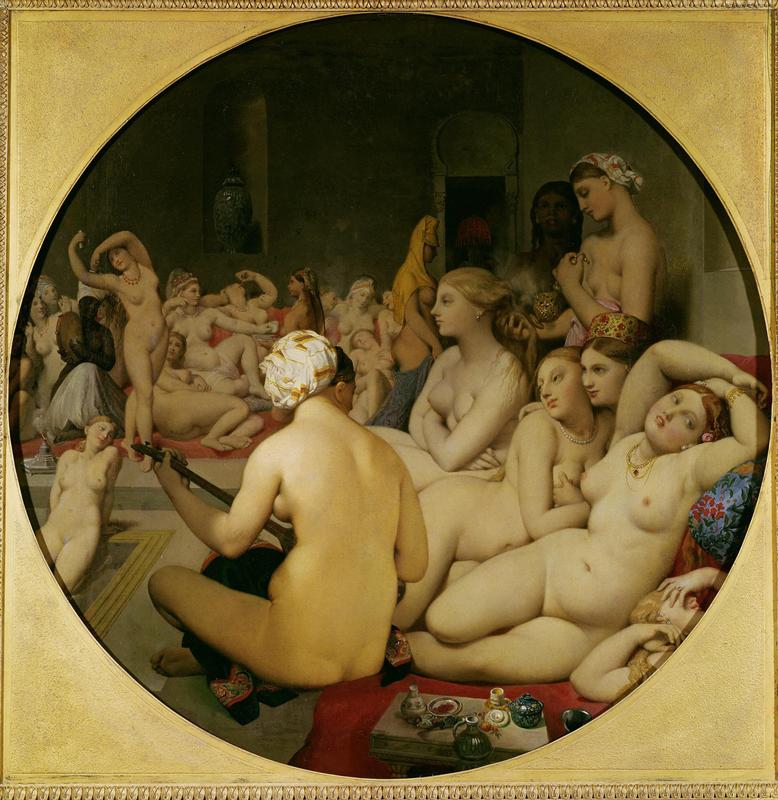

Figure 8. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, The Turkish Bath. Oil on canvas. Repository: Louvre. Wellesley College Visual Resources Collection

Europeans in Jerusalem and the Middle East

Europeans had traveled to the Holy Lands as early as the 1095, when the Western Europe initiated the Crusades in order to spread the influence of Christianity to the Near and Middle East.1 However, the main reason behind these military invasions was the securing of land and expansion of territories. The objects brought back from the Near East during the Crusades left as long-lasting impression and desire for non-western treasures. The acquiring of Near Eastern Christian art also allowed these European nations to Westernize Christianity and to develop correlations between Biblical history and the power of European civilization. The acquiring of ancient Near Eastern and Mesopotamian objects by European government sponsored groups also began for similar reasons. Both of these acquisitions reflect the act of intellectual imperialism; an example of this is when European nations believe that by aligning themselves with the cultural and intellectual success of Near Eastern civilizations, they are contributing to their own legacy as a world superpower. Initiated by the Crusades, travel to the Middle East continued well into the future as Grand Tour travel developed, driven by the same desire for foreign treasures and goods.

Similar to Grand Tour traveling in Italy and Greece, expeditions to the Holy Lands required wealth in order to finance the journey and diplomatic connections to travel in the Middle East. Most travelers were either European scholars trying to acquire knowledge or aristocrats vacationing in search of the allure of the Orient. In 1756 Patrick and Alexander Russell, physicians in the Levant Company in Aleppo, published The Natural History of Aleppo.2 Also known as the Turkish Company, the Levant Company was a British trading firm that had been operating in the area with the permission of the Ottoman government since 1581.3 The Russells’ roles in the Levant Company provided them with access to travel in Syria, allowing them to collect data on local customs, flora, and fauna. Solely Alexander Russell published the original edition of Aleppo after his travels in Aleppo and his brother Patrick published the second edition after his death in 1768; the second edition “also includes paintings by the famous Anglo-Egyptian flower painter George D. Ehret” and numerous illustrations.4 The first volume of Aleppo provided simple descriptions of the inhabitants of the city and its physical features. The second volume expands upon this by including a “natural history, descriptions of Syria and Aleppo, with much detail on domestic culture, manners, and customs, monuments and common diseases, including a vivid description of the effects of smallpox.”5

As the Director-General of Museum in France, Auguste de Forbin was able to travel to the Middle East not only as a French aristocrat. While on his expedition to re-collect for the Louvre’s antiquities collection, he toured Palestine in October of 1828 and arrived in Jerusalem late November; while there he also toured the Jordan River, the Dead Sea, Jericho, and Bethlehem.6 In Jerusalem he produced several sketches and paintings of the city and scenery; he most notably drew architectural sketches of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and painted a view from the Josaphat Valley.7 These aristocrats would also often travel to North Africa and Egypt. Auguste de Forbin also journeyed to Cairo after exploring Jaffa and Gaza. As a European viewer in Egypt, Forbin was mesmerized by the vibrancy of Cairo’s street life, and was drawn to Turkish baths and Islamic architecture and monuments. He also sketched and gazed upon the glory of the Giza Pyramids, the ruins at Luxor, and the temple of Amon.8 Grand Tour travel in Egypt has also resulted in the acquisition of Egyptian artwork by prominent European museums such as the British Museum. Egypt presented the allure of a civilization as great as the Greco-Roman Empire; this admiration for Egyptian civilization and the excavations of this African country led to the conflation of Egypt as a classical civilization rather than an East African civilization. Grand Tour travel beyond Europe resulted from Euro-Western superpowers’ growing involvement in trade and diplomatic pursuits throughout the Middle East.

Exoticism and Identity Formation in Greece and the Middle East

While Greece is a symbol for the glory of classicism and the beginning of Western civilization, it is also “a threshold to the Orient.”9 Greece not only represented the ideal Classical civilization, it also conjured images of Near Eastern and Mediterranean cultures. To some Europeans, Greece became more of an ideal or utopia, rather than a physical destination. Similarly, any nations beyond Greece in the Near East became wrapped up in Orientalist fantasy and ideology. In 1716, Lady Wortley Montagu traveled with her husband to Constantinople and other destinations in the Near East.10 During this journey, Lady Montagu wrote in a series of travel journals documenting her experience with “the Orient,” or non-European cultures in the Middle East; due to this, some scholars consider her “the founder of Orientalism.”11 While in Constantinople, Lady Montagu would often disguise herself in the garbs of local Turkish women and visit the Turkish baths; Her letters became the foundation for Orientalist art, such as Ingres’s Le Bain Turc or The Turkish Bath (Fig. 8). Her writings also represent the idea of the harem and its influence over the imagination of curious Europeans. Travel journals and publications are paramount to understanding the origins of Orientalism in Europe; tales spun from these travels also informed Western imaginations about foreign gender roles and sexuality. Harems and harem culture soon became synonymous with the Middle East.12 During his journeys as the Director-General, Auguste de Forbin was supposedly “seduced” by the city life in Cairo and its exotic harems. Resulting from his desire to capture it in his sketches and paintings, Forbin often visited communal baths, Islamic monuments, and even a slave market. Notions such as these contribute to European fantasies surrounding the Middle East and conflate societal differences between the two geographic regions.

Written testimonies of travel in the Middle East became the inspiration for many artists using harems scenes in their artworks. William Hogarth’s A Turkish Bathserved as an illustration inAubry de La Motraye's "Travels throughout Europe, Asia and into Part of Africa” (Fig. 5). A Turkish Bath depicts two women, one dark-skinned and the other light-skinned, bathing together; the darker-skinned woman is actually washing the lighter-skinned woman creating a mistress-servant relationship between the two. Images such as A Turkish Bath contributed to promoting a hypersexualizaed image of non-European women throughout the west. Claude Augustin Duflos le Jeune’s Sultana Reading in the Harem presents an extremely different image of the harem (Fig. 6). Sultana depicts a woman reclines on a chair leisurely while reading a book in a classically decorated room. While the columns and exquisite drapery in this image reads as European, the artist also portrays non-western men outside of the room at the far left of the image; the foliage in the background reads as non-European because it is reminiscent of the lush, tropical plants. This image romanticizes the harem while still employing non-western iconography to attract the curiosity of a European viewer. The print A Turkish Lady at the Bath also depicts lush images of foreign locales, capturing the attention of a western audience. The Grand Tour in the Middle East resulted in exoticized images of non-Western peoples circulating throughout Europe, furthering the creation of the non-European other and the Western curiosity for all things foreign.

1. Penny J. Cole, The Preaching of the Crusades to the Holy Land, 1095-1270 (Cambridge: Medieval Academy of America, 1991), ix.

2. Charles Foster, ed, Travellers in the Near East, (London: Stacy International, 2004), 29.

5. Charles Foster, ed, Travellers in the Near East, (London: Stacy International, 2004), 35.

6. Ibid., 109.