Robert in Rome

Hubert Robert,The Old Temple, 1787-88, oil on canvas (Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois)

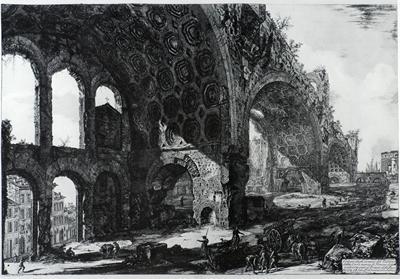

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, "Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine" from Vedute di Roma, 1757, etching (Davis Museum at Wellesley College, 1999.0.407)

Hubert Robert,T he Nymphaeum of the Villa di Papa Giulio, Rome, ca. 1761, red chalk, with framing lines in pen and brown ink (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York)

Robert arrived in Rome in 1754 with the retinue of the comte de Stainville (later to become the duc de Choiseul) (1719-1785), who was the son of his parents’ employer, the marquis de Stainville. The younger Stainville, had just been appointed French Ambassador to the Holy See, and was able to use his influence to procure Robert’s acceptance into the Académie de France in Rome, even though Robert never received the Prix de Rome, a prestigious scholarship which provided arts students the opportunity to study in the city. Stainville was Robert’s primary protector until 1759, when Robert was appointed pensionnaire in the Académie. His appointment was obtained through yet another powerful connection: Abel-François Poisson (1727-1781), the marquis de Marigny and brother of Madame de Pompadour (1721-1764), Louis XV’s prominent mistress. Poisson had recently been elected director general of the King’s buildings.

During his time at the Académie, Robert, who had a taste for architecture, studied the antiquities and modern monuments of Rome. He was also able to meet two artists who became his mentors and had very significant influences on his artwork. The first was Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691-1765), who was one of Robert’s professors. Panini himself was already a great master of the architectural capriccio, which were fantasy landscapes that brought together several different monuments and buildings into one composition. It was likely under Panini’s mentorship that Robert began to develop his own style of capriccio, which he is now most known for. Scholars even speculate that Robert may have contributed to Panini’s series Views of Ancient and Modern Rome (1757), which also happened to be commissioned by the comte de Stainville.

In addition to studying under Panini, Robert received mentorship from Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), the renowned and prolific vedutisti, whose studio was located directly across the street from the Académie. Piranesi’s etchings served as further inspiration for Robert’s famous capriccio. In looking at Robert’s painting The Old Temple (1787-1788) and comparing it to one of Piranesi’s etchings, Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine (1757), one can see that Robert makes use of the same (albeit less dramatic) one-point, diagonal perspective that Piranesi utilizes in so many of his works. Additionally, both works heighten the monumentality of the structures they are depicting by lowering the viewer’s eye and inserting small, almost minute, human figures in the foreground for comparison. The vegetation growing in and around the aging temple and the ruined basilica helps to further highlight and dramatize their levels of decay.

During his time in Rome Robert also met and befriended the French painter, Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806). Robert, Fragonard, and another artist, Abbé de Saint-Non (1727-1791), traveled through southern Italy, creating many drawings along the way, such as The Nymphaeum of the Villa di Papa Giulio (ca. 1761). Robert often did these works in situ, going to great lengths in order to view his subjects from specific angles, even if they required rather dangerous or precarious positioning. In his last three years in Rome, perhaps in anticipation of his return to Paris, Robert produced a significant amount of drawings, which included the ten piece series, Les Soirées de Rome (1763/1764). Later on in his career, long after leaving Rome in 1765, Robert would continue to refer to these drawings when painting images of the city.

SYL

_____________________________________________________________________________________

1Nina L. Dubin, Futures & Ruins: Eighteenth-century Paris and the Art of Hubert Robert (Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute, 2012), 166.