Renaissance to Modern Age

Photo taken by Robert Macpherson in 1860 of the Pantheon. This photograph shows the Pantheon prior to the removal of the bell towers, with the Egyptian obelisk and fountain directly in front.

Davis Museum, Wellesley College.

In 1575, Gregory XIII commissioned a fountain by Jacopo della Porta to put into the center of the Piazza della Rotonda. Clement XI erected the Egyptian obelisk, one of many in Rome, above the fountain in the early 1700s.

The 17th century brought about significant changes for the exterior and interior appearance of the Pantheon. The porch was regularly renovated and maintained, until Pope Urban VIII Barberini stripped its bronze beams to make weaponry.1 This was only one example of the common practice of despoiling Roman monuments of their bronze. Barberini attempted to appease the upset public, stating that the bronze was actually intended for Bernini’s Baldacchino. He also commissioned Francesco Borromini to design a timber replacement for the beams and a proper column to replace the unsightly brick wall in the portico.2

Of all the additions, however, Pope Urban VIII’s decision to add two bell towers was by far the most drastic. The central bell tower, which had been added in the Middle Ages, was removed and replaced by two others set above the intervening pediment. This significantly altered its appearance and elicited negative reactions from the public: soon people began calling the towers the “ass’s ears”. Though Carlo Maderno and Borromini were responsible for the design, somehow the bell towers became misattributed to Bernini.3 We still do not know why or how this association came to be, but many still label the “ass’s ears” as Bernini’s unfortunate creation.

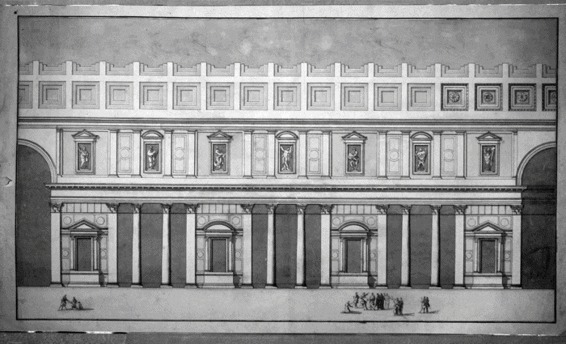

Paolo Posi's controversial design for the Pantheon's attic. Done in the elaborate 17th century style, it conformed more towards Carlo Fontana's idea of the Agrippan Pantheon rather than on actual ancient design.

In the early 18th century, Clement XI placed a marble high altar in the rotunda.3 The marble was taken from Domitian’s palace.4 A few decades later, architect Paolo Posi completely redesigned the upper stage in the rotunda in the popular style, leading to much criticism about regarding his design’s non-conformity to its original ancient aesthetic.5

In the middle of the 19th century, Pius IX removed the bell towers and replaced the dull inscription letters with new bronze; his efforts returned the Pantheon closer to its traditional appearance. He also extended the Via della Palombella in the late 1800s, clearing the buildings that had covered much of the Pantheon’s back structure.6

1 Tod Marder, "The Pantheon in the Seventeenth Century," in The Pantheon, ed. Marder and Jones, (New York, NY: Cambridge UP), 298.

2 Ibid., 300.

3 Ibid.

4 Licht, The Rotunda in Rome, 242.

5 Ibid.

6 Susanna Pasquali, "Neoclassical Remodeling and Reconception," in The Pantheon, ed. Marder and Jones, (New York, NY: Cambridge UP), 349.

7 Licht, The Rotuda in Rome, 243.