"Egyptian" Exterior & "Roman" Interior

An “Egyptian” Exterior

A variety of tomb shapes were possible for those who could afford it: houses, temples, benches, round tombs, square tombs, tower tombs, etc.1 Why did Cestius choose a pyramid? It was constructed approximately 12-18 years after Rome’s annexation of Egypt in 30 BCE. Is the pyramid a visual expression of admiration for Egyptian religion and culture? A celebration of Augustus and Aggrippa’s successful military expansion? Ancient Roman imperialism, colonialism, and orientalism? 2

It’s impossible to answer any of these questions with certainty, but we can begin with the fact that the pyramid shape was legibly “Egyptian” and widely understood by the Roman viewer as “fit for a king.”3 For the Romans, “Egyptian” was equivalent to “ancient” and “eternal.” The Pyramid Age was more ancient to the Romans than the Romans are to us.

Claridge theorizes that Cestius could have served in the Roman military in Nubia (annexed by Rome in 24 BCE), where pyramids for private individuals were not uncommon.4 It is possible, but Egyptomania was already having a profound stylistic influence on Roman art and architecture, and it does not necessarily mean that Cestius had a personal connection to Egypt.

In Pompeii, around the same time, domestic frescoes were reflecting the fad, as well. The Black Tablinum (Room 2) in the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii has a thin predella register decorated with scenes of Egyptian-looking deities and animal worship.5

A “Roman” Interior

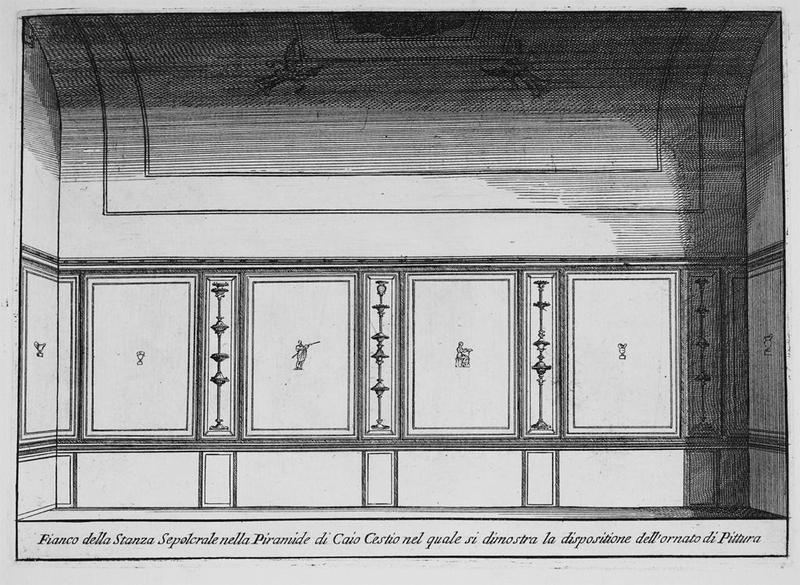

While the outside of the tomb is distinctly Egyptianizing, the inside of the tomb is stylistically “Roman.” The inner chamber has a barrel vaulted ceiling and is decorated with fresco paintings. Figures and vessels are suspended against flat, white backgrounds, which are divided by spindly architectural motifs. The preciously detailed surface ornament and ample negative space is characteristic of the Third Style of fresco painting.6

The ceiling features four identical nikai, winged personifications of victory, with laurel crowns in hand. They appear at the four corners of a square, which may have once contained an image but was destroyed by tunneling looters. The figures on the walls are women in Roman attire. One stands with a plate of food and a small pitcher (possibly filled with wine). Another stands at ease, holding the pipes of an elongated wind instrument in each hand. A third is seated, reading from a tablet. The fourth figure is a little more difficult to understand. She is seated and dipping her fingers into a basin. These figures may represent elements of a Roman feast or perhaps even a ceremony in a mystery cult.

-

Valerie Hope, Death in Ancient Rome (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2007), 147.

-

Molly Swetnam-Burland, Egypt in Italy (Cambridge University Press, 2015), 83.

-

ibid, 85, 88.

-

Amanda Claridge, Judith Toms, and Tony Cubberley, Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 399.

-

John Clarke, Houses of Roman Italy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 144.

-

Department of Greek and Roman Art, “Roman Painting,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004), http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ropt/hd_ropt.htm.