Inscriptions & Sumptuary Laws

The pyramid has several inscriptions, including one added 1,700 years later. The nomen and titles of Gaius Cestius are inscribed on both the northwestern and southeastern pyramid faces. The southeastern side also includes the execution of his will and the restoration of the monument in the seventeenth century. The latter inscription does do the helpful work of recording the life of the monument post-antiquity, but the linguistic and stylistic uniformity of the inscriptions could be misleading to a non-Latin-reading viewer in 2016.

Inscription on both northwestern and southeastern faces:

G · CESTIVS · L · F · POB · EPVLO · PR · TR · PL

Gaius Cestius Epulo, son of Lucius, of the Pobilia voting tribe, Praetor (chief magistrate), Tribune of the Plebs, Septemvir (one of seven) of the Epulones (priests in charge of public banquets in honor of Jupiter and other religious festivals).

Inscriptions only on the southeastern face:

OPVS · APSOLVTVM · EX · TESTAMENTO · DIEBVS · CCCXXX

ARBITRATV

PONTI · P · F · CLA · MELAE · HEREDIS · ET · POTHI · L

The work was completed, in accordance with the will, in 330 days, by the decision of the heir [Lucius] Pontus Mela, son of Publius of the Claudia, and Pothus, freedman.

INSTAVRATVM · AN · DOMINI · MDCLXIII

Restored in 1663 the year of our Lord

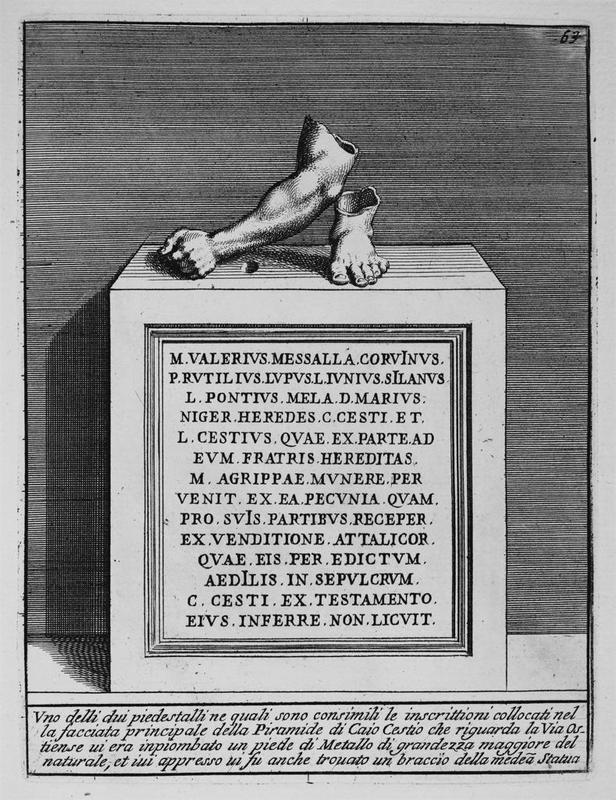

In 1655, the west side of the pyramid was excavated revealing two inscribed marble statue bases and two columns which were re-erected at the western corners of the tomb (inscription below).6 Though these statues have been lost, their inscriptions tell us that his heirs, including general and consul Marcus Agrippa, paid for them using “that money which they received according to their own shares from the sale of the attalica which it was not permitted to them to bring into the tomb of Gaius Cestius according to his will, according to the edict of the aediles.” Put simply, because they were legally blocked from putting gold-embroidered fabric (the attalica) in the tomb because of sumptuary laws, the heirs sold the fabric and used the funds to set up the statues instead.2 Around the time of Cestius’ death, the aediles were (through edicts) enforcing sumptuary laws more strictly.

Sumptuary laws, which limit ostentatious displays of wealth and luxury, can be traced back to the foundational Twelve Tables of of Roman law in the mid-5th century BCE. They applied to feasts and clothing, as well as funerals and tombs.3 Table X, part 8 explicitly states “no gold shall be added to a corpse,” though the burial of gold fillings could occur “without prejudice.”4

Inscription on the statue bases:

M · VALERIVS · MESSALLA5 · CORVINVS ·

P · RVTILIVS · LVPVS · L · IVNIVS · SILANVS ·

L · PONTIVS · MELA · D · MARIVS ·

NIGER · HEREDES · C · CESTI · ET ·

L · CESTIVS · QVAE · EX · PARTE · AD ·

EVM · FRATRIS · HEREDITAS ·

M · AGRIPPAE · MVNERE · PER ·

VENIT · EX · EA · PECVNIA · QVAM ·

PRO · SVIS · PARTIBVS · RECEPER ·

EX · VENDITIONE · ATTALICOR ·

QVAE · EIS · PER · EDICTVM ·

AEDILIS · IN · SEPVLCRVM ·

C · CESTI · EX · TESTAMENTO ·

EIVS · INFERRE · NON · LICVIT ·

______________________________________________________________________________

-

Amanda Claridge, Judith Toms, and Tony Cubberley, Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 399.

-

Molly Swetnam-Burland, Egypt in Italy (Cambridge University Press, 2015), 87.

-

Table X, part 3 limits the number of mourners and performers at one’s funeral.

-

The Twelve Tables, trans. Johnson, Coleman-Norton, and Bourne, (University of Oklahoma: 1961), 6.

- It may be of interest that Messalla was the uncle and guardian of Sulpicia, one of the rare women whose writing survives from ancient Rome.

- Amanda Claridge, Judith Toms, and Tony Cubberley, Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 401.