The Greco-Roman Debate/Della Magnificenza

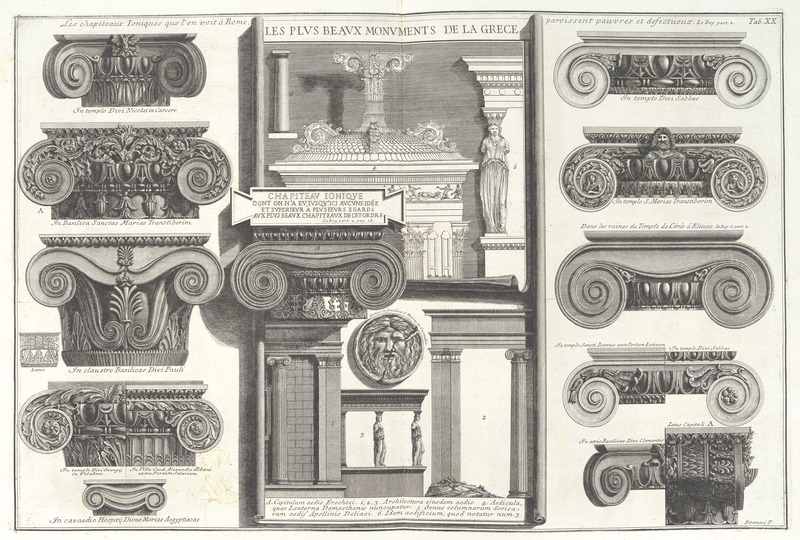

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Various Roman Ionic capitals compared with Greek examples from Le Roy from Della Magnificenza e d'Architettura de'Romani, ca. 1750, engraving (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Piranesi, in his engagements with foreigners, stumbled into a controversy with Irishman James Caulfeild, Lord Charlemont (1728-1799) known as a high profile Grand Tourist through Pompeo Batoni’s portraits of him. He was a formidable patron in the Roman art-dealing and commissioning circles. He rejected the work he commissioned from Piranesi due to timing and payment issues. Piranesi, in response, created a number of engravings, including one of a winged serpent eating its tail, entwined with an engraver’s stylus. Symbolizing the eternity of Piranesi’s art, the serpent and the stylus also raise discussions on various topics ranging from a commission gone wrong to thoughts on the nature of the engraver’s art and its place in history. In addition to this controversy, Piranesi could not help himself from being brought into the debate over Greek versus Roman superiority.35 This debate is contextualized by the founding of modern archeology and ancient art history by Johann Winckelmann (1717-1768). Winckelmann was the first art historian to make the distinction between Greek, Greco-Roman, and Roman art, leading to controversial debates about which was the superior society. He supported the achievement of Greek invention, while Piranesi was a leading advocate for the preeminence of Roman architecture. Piranesi felt compelled to create the Della Magnificenza as a defense of Roman architecture. The Della Magnificenza ed Architettura de Romani (1761) involved a sequence of illustrations depicting Roman invention backed up with intelligent text. In the image of various Roman Ionic capitals compared with Greek examples, Piranesi directly demonstrates his view that Roman technology was superior to Greek. His main thesis was based on the idea that the Romans had learned not from the Greeks, as British and French scholars argued, but from the earlier inhabitants of Italy, the Etruscans.36 He praised the severity of Etruscan architecture, which was continued in the utilitarian engineering of Rome, and the superiority of Etruscan invention.37 This controversy affected Piranesi’s business severely and gave him a dishonorable reputation as someone who was outspoken and rude, and often appeared arrogant.38

____________________________________________________________________________________

35Donato, “Fresh Legacies,” 508-511.

36Denison, Rosenfeld, Wiles, Exploring Rome: Piranesi and his contemporaries, 17.

37Lucchi, Lowe, Pavanello, The arts of Piranesi, 53.

38Denison, Rosenfeld, Wiles, Exploring Rome: Piranesi and his contemporaries, 19.