The Grand Tour

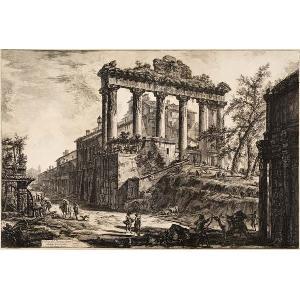

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Temple of Saturn, plate 80/1 from the series "Vedute di Roma" (Views of Rome), 1774, etching (Davis Museum)

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Sepolcro di Cecilia Metella (Tomb of Cecilia Metella), plate 112 from the series "Vedute di Roma" (Views of Rome), 1762, etching (Davis Museum)

The Rome Piranesi saw for the first time in 1740 was a Rome whose appearance had changed greatly over the past decade. Before Piranesi had traveled there, Rome had undergone a period of urban development, in artistic as well as in economic terms.23 The initial impact of Rome was both exhilarating and frustrating for Piranesi. On the one hand, there was the unlimited visual excitement of the city, which was still medieval in the close-knit network of narrow streets, fountains, obelisks, and large churches. On the other hand, the opportunities for an ambitious young architect like Piranesi were practically non-existent.24 It was mainly the tourists who gave life to the cultural scene in Rome and whose lavish spending stimulated the economy, leaving little room for budding architects like Piranesi. Rome, as the capital of the ancient empire, was the focus of the Grand Tour. While Roman society itself was stagnant, the popular tourist centers brought a life to the city, making Rome an important meeting point for the exchange of creative ideas. Tourists from all over Europe came to study the antique architecture and highly acclaimed masterpieces of the 16th century, as well as the city’s contemporary art.25

Piranesi, as demonstrated by his work on the Antichità Romane, was highly intrigued by the ancient Roman past, similar to the passions of Grand Tourists. His enthusiasm for antiquity was inspired by his older brother, Angelo (circa. 1720). His brother, then a practicing Carthusian monk, used to read to Piranesi the heroic account of Rome’s origins in the histories of Livy when they were children. These histories piqued Piranesi’s lifelong obsession with the antiquities of Rome.26 He had an enduring relationship with antiquity and translated antique style into a vernacular, the vedute, that combined present context with the wisdom of styles past.27 Piranesi's vedute, or views, were sold as souvenirs to Grand Tourists. The vedute were focused on the most popular sites for Grand Tourists, as that was Piranesi’s main audience. The Temple of Saturn and the Tomb of Cecilia were both ancient Roman sites that garnered attention from antiquarians. Both of these plates appear to be from Piranesi’s later etchings in the 1760s as, unlike his early work, they are less focused on the sweeping views of Rome and are more directed towards a single monument. Moreover, the etching is heavier and layered, depicting the vastness and crushing expanse of these monuments, an example of the sublime. Earlier in Piranesi’s career, his views, while from an unnatural and impossibly broad perspective, encompassed multiple monuments and a more expansive view of popular tourist sites. Piranesi’s views were prized among tourists as he stood out as a unique engraver and could quickly produce many copies of the same view.28 He transformed the veduta from a subtle Rococo vision of unattainable perspectives, as in the work of Giuseppe Vasi, to an uncompromising statement of the sublime, as seen in previous works like the Antichità Romane, over his time as an engraver.29

______________________________________________________________________________________

23Denison, Rosenfeld, Wiles, Exploring Rome: Piranesi and his contemporaries, 12.

24Lucchi, Lowe, Pavanello, The arts of Piranesi, 28.

25Denison, Rosenfeld, Wiles, Exploring Rome: Piranesi and his contemporaries, 37.

26Scott, Piranesi, 16.

27Clorinda Donato, "Fresh Legacies: Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Enduring Style and Grand Tour Appeal," Eighteenth-Century Studies 43, no. 4 (2010): 508-511.

28Scott, Piranesi, 17.

29Lucchi, Lowe, Pavanello, The arts of Piranesi, 29.