Le Vedute di Roma

![View of the Piazza della Rotonda [With the Pantheon in the background], from Vedute di Roma (Views of Rome), part I View of the Piazza della Rotonda [With the Pantheon in the background], from Vedute di Roma (Views of Rome), part I](http://omeka.wellesley.edu/piranesi-rome/files/fullsize/45ef6b3586291d503785f3a49a445394.jpg)

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, View of the Piazza della Rotonda [With the Pantheon in the background], from Vedute di Roma (Views of Rome), part I, 1750-1778, etching (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

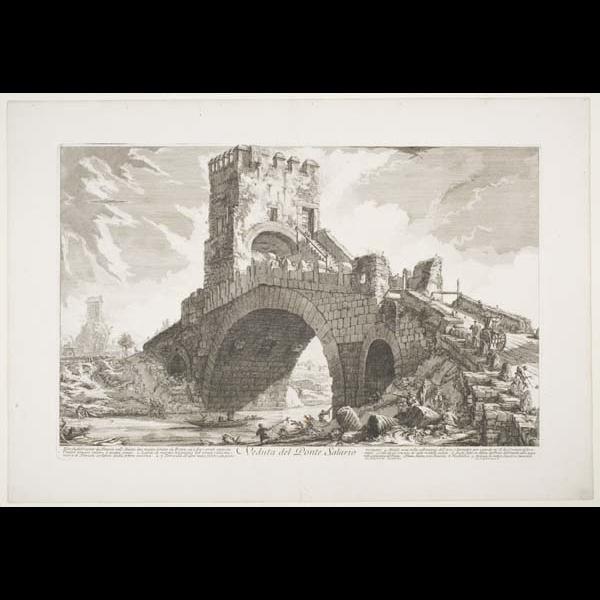

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Veduta del Ponte Salario (View of the Ponte Salario), plate 55 from the series "Vedute di Roma" (Views of Rome), 1754, etching (Davis Museum)

By 1747, Piranesi had begun work on the Vedute di Roma, and he continued to create plates for this series until he died in 1778. Piranesi’s Vedute, which overshadowed competitor’s views of Roman landmarks through compelling compositions, strong lighting contrasts, and dramatic presentation, shaped European conceptions of present day Rome. This influenced European thought to such an extent that Grand Tourists, who had come to know Rome through Piranesi’s prints, were recorded as being disappointed on their first encounter with the real thing.39 The views were intended as tourist souvenirs and, from their instant popularity, Piranesi had obviously judged the market well. His early sites include obvious popular sights, such as Piazza della Rotonda and the Sepolcro di Cecilia Metella. The first thirty-four views were published in a single volume and entitled Le Magnificenze di Roma. In his first views, the monument or subject was drawn from a distance so that it was clearly set in its context. The little figures present at the ground level are the everyday people and visitors in contemporary Rome. As represented in the “Veduta della Piazza della Rotonda,” Piranesi, clearly contorting perspective, etched an exaggerated and extended view of the Rotonda, unfocused on a specific aspect of the scene. His later views featured heavier line, a sublime eye, and more dramatic perspectives. They also specifically concentrate on a monument, like the “Veduta del Ponte Salario,” or ruin instead of portraying a sweeping view of Roman landscape. These changes could possibly be a response to market demand and what Grand Tourists wanted to see in their vedute, or it could be a personal style change as Piranesi became intrigued by the idea of the sublime. Nevertheless, these views of Rome firmly established Piranesi’s reputation and gave him the initial financial stability that enabled him to tackle grander themes. Moreover, Piranesi’s interest in ruins was genuine antiquarian desire to preserve and record.40 Piranesi was able to focus in on his awareness of what was noble and magnificent and gain a sense for the sublime in the architectural tradition of Rome. Piranesi’s lifelong obsession with architecture, past and present, was fundamental to his genius. His etched plates contained remarkable imagination and a practical understanding of ancient technology. They created a perception of antiquity lasting to our own time.41

__________________________________________________________________________________

39Thompson, "Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778).”

40Scott, Piranesi, 20-24

41Denison, Rosenfeld, Wiles, Exploring Rome: Piranesi and his contemporaries, 29.