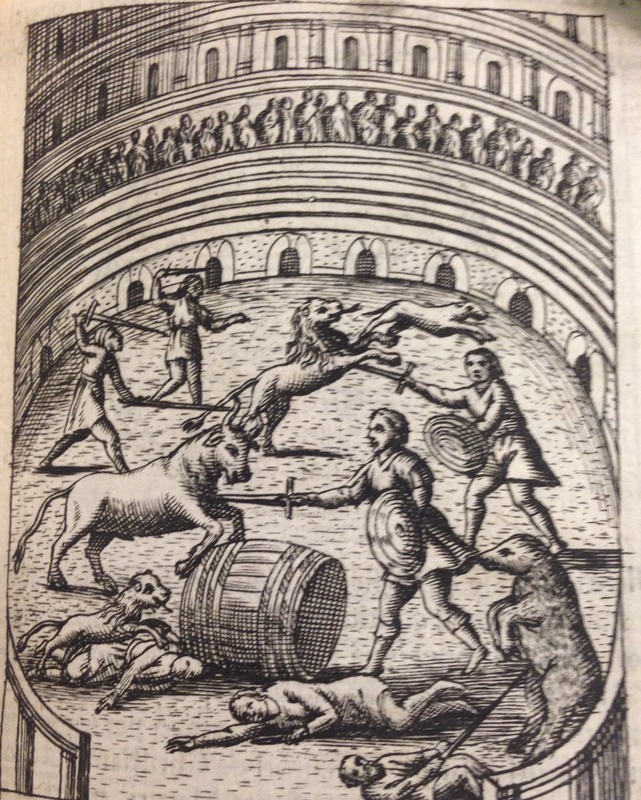

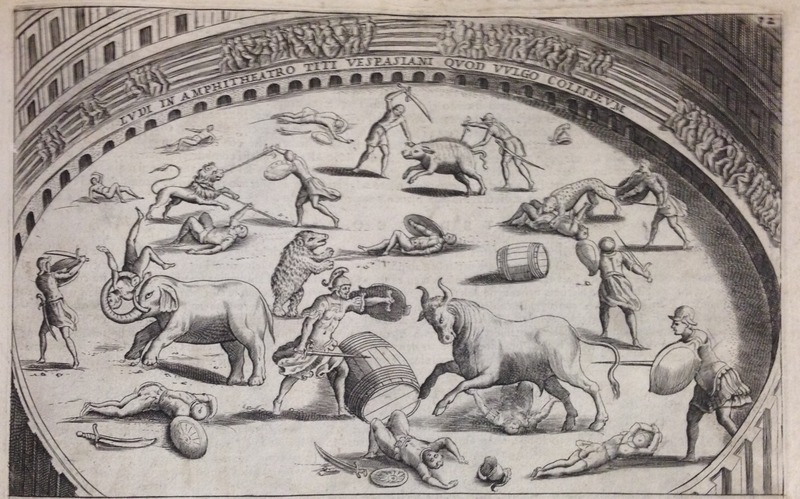

The Amphitheatre and Spectacle

Filippo de'Rossi's illustration of "Caccie nel Coliseo", or "Hunting in the Colosseum", from Ritratto di Roma antica (Rome, 1689). Wellesley College Special Collections.

The Colosseum was a politically and socially important structure in its time. The distinctly Roman architectural form served a distinctly Roman function: that of spectacula (Latin for "spectacles). For the Roman emperor in particular the Colosseum was a politically important space. The unique elliptical shape of the Amphitheatre both facilitated viewing of the arena's activities, and facilitated the citizens' view of their emperor.1 Not only could the emperor create the allusion of his own accessibility, which the Roman people needed to believe they had, but it also allowed the emperor to showcase his power and generosity.2 By throwing games and spectacles, the Emperor showed his citizenry that he cared about them, that he wanted them to be happy, and he allowed them the chance to (at least believe) in their collective influence over him with their chanting.3

Giacomo Lauro image of an animal hunt in the Colosseum, from Splendore dell'antica e moderna Roma (Rome, 1641). Wellesley College Special Collections.

So entangled was the concept of "spectacle" with the Colosseum, that Martial, a court poet for the Flavians, wrote a series of epigrams recording and commemorating the building and many of the events from the 100 days of inaugural games.4 According to Martial's first epigram from his work aptly titled "Liber Spectaculorum" (Book of Spectacles), the Colosseum itself was a spectacle to behold, beyond the wonders of the ancient world.5 The spectacle, however, did not stop with the immensity of the building. Martial talks of an uncontrollable lion that the emperor orders to death in his 12th epigram, demonstrating the power of the emperor to impose his will even upon wild animals. He also writes of an elephant in his 20th epigram, which kneels in reverence to the emperor without any training or cueing, thus affirming the emperor's inherent imperial power. There are countless moments within the epigrams of Martial's Liber Spectaculorum that document the ways in which various facets of the emperor's power and goodwill is displayed or affirmed within the arena.

__________________________

1 Keith Hopkins and Mary Beard, The Colosseum (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005), 40.

2 Hopkins and Beard, The Colosseum, 41.

3 Hopkins and Beard, The Colosseum, 40.

4 Filippo Coarelli, The Colosseum (Los Angeles: J Paul Getty Museum, 2001), 169.

5 Martial, M. Valerii Martialis Liber Spectaculorum, trans. Kathleen M. Coleman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 1.