Sculptures Discovered At Herculaneum

Seated Hermes, pre-79 AD, sculpture (National Archaeological Museum of Naples)

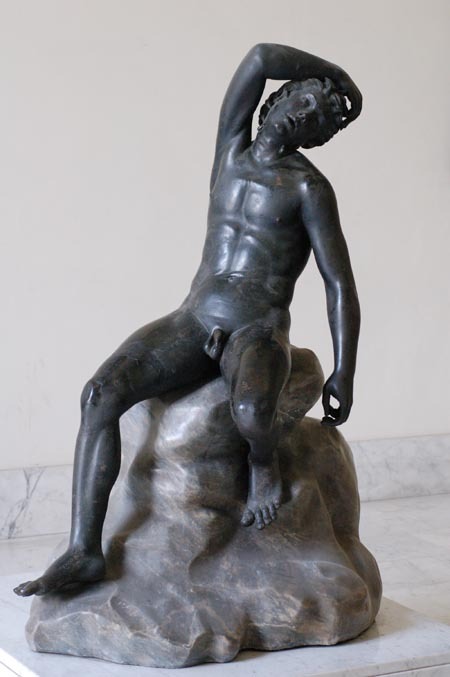

Sleeping Faun, 1st Century BCE, sculpture (National Archaeological Museum of Naples)

From bronze to marble, Herculaneum unearthed an incredible amount of artwork that illuminated 18th-century artists as well as common people. Even sculptures inspired the 18th-century thinkers; subjects that the ancient world created permanent figures out of, would be subjects to be discussed. As a whole, the sculptures show the religious fervor of Herculaneum, reflecting the ancient world precisely. Seated Hermes (Resting Hermes), one of the bronze sculptures discovered in the garden of the Villa of the Papyri portrays Hermes, Roman messenger God, seated and looking down. The sculpture was recognized as an imitation of an original Greek sculpture made a couple centuries prior, extremely telling of the great influence of the Greek civilizations on the Romans. The Villa of the Papyri also featured another recognizable sculpture, Sleeping Faun, showing a nude individual, head back and legs open.1 Both sculptures depict the male nude, a form of art highly emphasized in the 18th century, especially with the revival in antiquity. Along with history paintings, the highest from of art, one of which only those with the highest level of technique and skill could master, was the male nude. The discovery of the sculptures at both Pompeii and Herculaneum only intensified the popularity on this form of art regardless of the growing interest in painterly styles in the latter half of the 18th century.2

An even greater number of sculptures were found in the Theatre, that were among the earliest objects extracted in Herculaneum. Unlike some of the sculptures found in the Villa of the Papyri however, those found in the Theatre offered a rather different perspective of the classical age. Eighteenth century intellectuals were confounded by the sculptures of the Roman emperors; compared to the statues of the Gods that idealized the male body in its muscular details, those of the emperors did not idealize the male nude, but rather presented the human body realistically.3 This allowed classicists to learn more about ancient Roman’s relationship with their rulers during this time. One could discern from the artists of Herculaneum’s their portrayals of the Gods that the Romans were a polytheistic society intent on pleasing the Gods in everything that they did, with the hope that in return the Gods would favor them. On the other hand, by examining the statues of emperors, 18th-century audiences gained more information about the rulers of the classical time period, and how they were questionably not as respected as Gods.

-SC

______

1. Goran, Blix, From Paris to Pompeii: French Romanticism and the Cultural Politics of Archaeology, (Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 17, accessed May 8, 2017, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46nqjk.5

2. Blix, 11

3. Joseph Jay, Deiss, Herculaneum: Italy's Buried Treasure. (New York: Harper and Row, 1985), 178-179